A quail of a tale in Pakistan

Damon Lynch

Depending on the intensity of the traffic and the state of repair of the Grand Trunk road, the village of Pabbi is about 45 minutes from Peshawar in the Northwest Frontier Province (NWFP) of Pakistan. Among NWFP’s valleys and fertile plains are found idyllic villages. Here life is agricultural, governed by the coming and going of the seasons. Crops in golden fields sway gently in the breeze. Tall elegant trees line paths between villages and fields. Sporadically a lovingly tended garden resplendent in flamboyant color bursts forth amidst the muted browns and greens that dominate the landscape. Hardly a sound can be heard apart from nature’s gentle soothing charms. Pabbi is not such a village. It assails the senses as a city does, her raucous markets teeming with people, and buses and vans and trucks and most especially rickshaws spewing out noxious exhaust fumes, soot and dust. A garish hand painted sign dominated by a giant set of teeth advertises a dental practice; beneath it tired donkeys trot past baring their own teeth at blows from the sticks of their masters. Squashed vegetables and fruits litter the roadside. Garbage festers in open drains, the acrid stench of their dank waters mingling with the biting smells of cooking wafting over the imposing walls of secluded homes.

<

Pabbi may have the body of an adolescent city, but the cultural blood flowing thickly through her veins is pumped by a rural heart. Vast loosely extended families cluster alongside various lanes and roads of the village, linked by forgotten marriages of years gone by. People rise early in the morning. Crops are tended in fields scattered throughout the village, becoming more abundant further away from the main road.

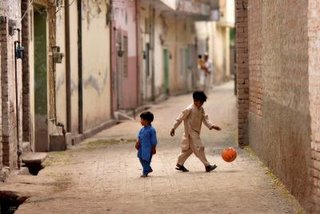

In Pabbi females and males are profoundly segregated from a budding age until death. Only children are free to see whom they please. Females are enveloped by flowing burkas whenever they go into the streets. Some men call the burkas shuttlecocks, for when they are white--as they often are--the resemblance is striking.

Girl in alley, Pabbi

Girl in alley, PabbiRefugees from Afghanistan have made their home in between the seams of interlocking family units in Pabbi, where despite the gangs they have formed and occasional police raids, life is safer and more prosperous than in Afghanistan. Although like the locals they too are Pukhtuns, locals refer to them as Afghans, noting that someone must be an Afghan if they are unable to locate where in the village the locals live.

As Pukhtun culture dictates, wives move in to live with their husbands in large family compounds, where brothers share the same compound as their parents. In the sanctity of the home gender demarcations rigidly and stubbornly retain their force, with brothers barred from laying eyes on their sisters-in-law even in progressive families. From one generation to the next the marriage of first cousins is especially common--birth defects are a subsequently reality in some families. Despite this danger marriages between cousins remain popular, not only to secure the financial standing of the family and because of limited social opportunities for young men and women to meet one another, but also because people who are not known cannot be trusted.

more reading

On the edge of consciousness: A quail of a tale in Pakistan